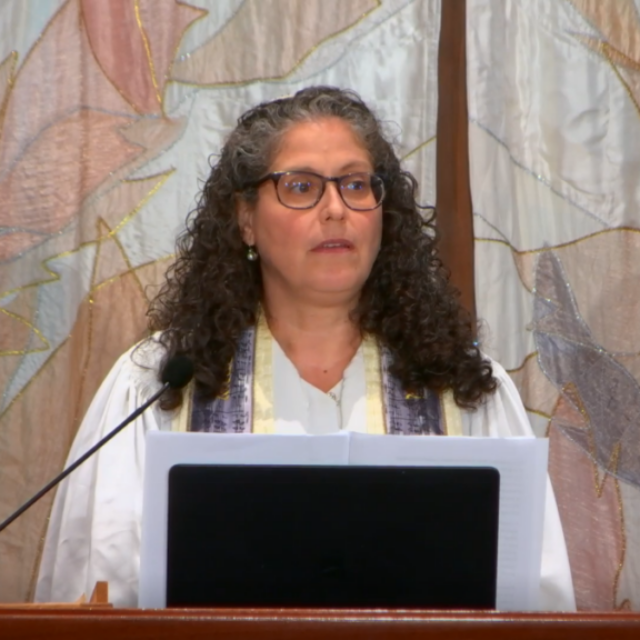

Holding On and Letting Go

Sermon by Rabbi Sarah H. Reines on Kol Nidre, 5782

September 15, 2021

Sermon Text:

Five years ago, after the US women’s gymnastics team won gold in the 2016 Olympics, the fire alarm rang in their Rio apartment complex. Simone Biles, still wearing the smile of a champion, grabbed her gold, and led her teammates out of the building, as she had led them to victory the night before. She had worked long and hard for that medal, and she was holding on to it.1

A month ago, at the 2021 Olympics, Biles shocked the world when she pulled out of the team competition, citing the “twisties,” a mental disconnect. Lost in midair, she had no sense of which way was up, and which way was down. Performing under these conditions would threaten her teammates’ chances at a medal, and more importantly, would threaten her physical safety and future.2

Simone Biles, who knows how to grab hold of the bar, the beam, the vault – at the precise angle, in the precise moment – who flips and flies thru the air with superhuman strength and agility, has now shown us, both on and off the apparatus, the power of knowing when to hold on, and when to let go.

Simone intuits this balance through her talent. But she has honed this skill after years of training and life experience. Perfecting the rhythm of grab and release isn’t easy. It takes practice. This is why, as the gates of the new year open and the gates of the past year close, Judaism has us take an accounting of our lives – directing us to seriously consider what we want to carry forward and what we want to leave behind.

Tradition helps us do this by urging us to face our mortality, having us reenact our entire life’s journey over these ten days. We move from Rosh Hashanah, the day we are born anew, to Yom Kippur, this day when we rehearse our deaths—no food, no drink, no creature comforts. This compacted life-span brings into focus the preciousness and precariousness of our existence. Poet, Yehuda Amichai, captures this in a few words, imagining the dates that will be on his tombstone. He writes:

Just a hyphen separating them.

I hold on to the hyphen with all my being.3

Picture it—hanging on to that high bar hyphen which is our life. We will swing from day to day with much greater ease if we fortify ourselves with what strengthens us, and free ourselves from what drags us down. So on this sacred night that invites us to change, let’s spend a bit of time reflecting on when to hold on and when to let go. And let’s consider how we do this as a community, in our shared experiences, as well as individuals, in our personal lives.

When clearing out closets and struggling with what to keep and what to discard, the organizing guru, Marie Kondo, suggests we hold each item, take a moment, and ask ourselves, “Does this spark joy?” Now that might work with clothes and chochkes, but there are more powerful reasons for us to decide to hold on.

Simone, history’s most decorated gymnast, was already known as GOAT, Greatest of All Time. So why did she train for years to participate in a second Olympics? Clearly, she loves her sport. But she had other motivation.

Simone is one of the hundreds of girls and teens sexually abused by Larry Nassar, former physician for the US gymnastics team. And she is the only high profile survivor still competing. She wanted to keep us focused on his crime and to prevent the US Gymnastics governing body from brushing their complicity to the side. She was determined not to let this depravity disappear from public consciousness. In Simone’s words: “I felt like I had a purpose, to be a voice for the younger generation, to have change happen. I feel like I’ve done that… like God called me.”4

The question, “Does it spark joy?” would have fallen short for Simone in deciding whether to keep competing or not. Decisions about what we hold on to are not always about our personal joy, but about what matters. Simone’s motivation to continue returning to competition, and our decision to return to High Holiday services, may be better articulated by a character in the novel, Here I Am by Jonathan Safran Foer. A 13 year old boy, speaking at his bar mitzvah service, reminds his congregation and ours, “You only get to keep what you refuse to let go of.”

Not every B’nei Mitzvah student that teaches from this bima speaks with the precocious wisdom of an acclaimed author. But each of them, and all children who celebrate becoming B’nei Mitzvah, are doing something far more important – they are representing families who have refused to let go of Judaism. And that is no small thing.

Every time any one of us holds on to Judaism in any way, we make a difference. A college student hangs a mezuzah in their dorm room, a family collects extra change in a tzedakah box – it matters. We work with HIAS, the ADL in pursuing justice – it matters. We visit a synagogue, join a synagogue – it matters.

Consider this Hasidic Holocaust tale, which blends fact and fantasy. A rabbi and his friend, imprisoned in a labor camp, stand with the other inmates before an enormous pit which will become their mass grave. The guards taunt and torture the prisoners, saying they can save their lives by leaping across to the other side. The rabbi and his friend survive to tell the story.

Some time later, the friend asks the rabbi how he was able to do the impossible: leap across that enormous pit, without falling to his death. The rabbi answered, ”I was holding on to my ancestral merit. I was holding on to the coattails of my father, and my grandfather, and my great-grandfather, of blessed memory.” Then the rabbi asked, “My friend, how did you reach the other side of the pit?” His friend answered, “I was holding on to you.”5

By joining together for Yom Kippur tonight, we are holding on to our ancestors’ coattails and to each other.

Engaging with Judaism comes easier to some than others, but it always takes effort. Hopefully your efforts strengthen you. They certainly strengthen the Jewish people. As we will read in Deuteronomy tomorrow, by holding on, you make a difference for everyone here this day, and everyone not here this day.

Does Judaism spark joy? I bet if we ask B’nei Mitzvah students practicing their Hebrew, or parents nagging their children to practice their Hebrew, or the cantor nagging parents to nag their children to practice their Hebrew… well, it’s not always a joyful exercise, kind of like the many hours Olympic athletes put in at the gym. These efforts often lead to joy, but more importantly, they strengthen and enrich us. Not letting go means our children and their children, and theirs and theirs and theirs, will have coattails to hold on to.

On to the personal struggle of discerning when to hold on and when to let go.

To explore this, let’s consider someone who might have been an Olympian, our ancestor, Jacob. He and his twin brother, Esau, were already wrestling in the womb. Esau crossed the birth canal with Jacob grasping his ankle. Jacob couldn’t shake coming in second, and spent his youth chasing his twin – grabbing Esau’s inheritance, Esau’s clothes, Esau’s name, and finally, Esau’s most prized possession: their father, Isaac’s blessing.

Esau’s anguished cry, “Father, don’t you have another blessing for me?” pierces through the centuries and stabs in our hearts still today.

Both brothers carried the intensity of their emotions for years, hurting themselves in the process. Esau’s justified anger became a yoke, controlling him and the way he moved through life. And Jacob spent decades trying to run from shame that clung to him wherever he went.

First, let’s look at Esau. After Jacob ran off with the gold medal blessing, Isaac eked out a consolation prize for his firstborn, saying, “When you decide to free yourself, you will release Jacob’s yoke from your neck.”6

Not the most comforting words for Esau to hear! I think it’s safe to assume Esau felt so destroyed that he couldn’t appreciate or absorb Isaac’s words for some time. An obvious hint is that he threatened fratricide, a weapon aimed at his brother, which wounded his parents, and certainly didn’t help his situation.

The text provides a quieter detail, often overlooked, revealing how in holding on to hurt, Esau harmed himself. After Isaac bestowed the blessing meant for him on his brother, Esau was consumed by a desire to do the impossible: undo the crime that had been done to him. He made a decision about who to marry, hoping to win back his father’s favor, hoping to restore his place in the family.

Maybe Esau had a happy marriage, maybe he didn’t. The point is that he made this impactful, personal decision while caught up in the grip of emotion, based on what he thought would please someone else. He was holding on to his fury so fiercely, that it held him in its clutches. He became a victim of his agony more than a victim of those who wronged him.

Now, let’s turn to Jacob. A Talmudic dictum teaches, “T’fasta m’ruba, lo t’fasta – If you take hold of too much, you hold nothing.”7 Jacob tried to fill himself with what was Esau’s, and still, that didn’t satisfy. Two wives, two handmaids, thirteen kids, masses of sheep, camels, cows, donkeys, rams, and immense wealth later, Jacob still couldn’t quiet the agitation that gnawed inside him. Fooling himself into thinking this was about possessions owed, Jacob asked Esau to meet up, and set aside a bunch of livestock, planning to pay his brother back in goods for the invaluable gift he had stolen, so many years earlier.

The evening before their reunion, Jacob, alone in the dark wilderness, wrestled once again.

This opponent was a mysterious stranger. The text introduces him from Jacob’s perspective as “ish – a man.” Later the stranger, himself, implies that he is a divine creature. Our sages describe him as an angel. Whoever, whatever he was, it was a tight match that lasted through the night.

This “ish”was strong! But Jacob, a natural competitor, had decades of training for this moment. As the sun started to rise, the stranger stole a page from Jacob’s playbook, and played dirty, wrenching Jacob’s hip.

Even the waves of excruciating pain couldn’t hold Jacob back. As my colleague, Rev. Barbara Brown Taylor writes, Jacob got hold of someone who smelled of heaven, and there was no way he was letting him go.8 He demanded the angel give him a blessing – one that he had worked for, had fought for. One that was meant for him.

The angel acquiesced, and disappeared with the dawn. Jacob emerged a victor, with a new name we still carry – Israel – a permanent injury, and an unabashed humility he never had before.

The saga of these twins is told from the perspective of Jacob. We don’t know if Esau had his own tussle with a heavenly creature. But as the narrative unfolds, it’s clear that Esau released the fury that fueled him years earlier.

Jacob limped toward Esau, pausing every few steps to bow deeply. Esau ran toward his twin, fell on his neck, and the last clinging fragments of Jacob’s shame fell away. There was no going back to the tangle of hurts and wrongs. The brothers simply held on to each other, and wept.

This embrace is a powerful picture of holding on after letting go. And if this was a fairy tale or a Netflix drama series, the story would have ended here. But this is Torah, which concerns itself with enduring truths rather than happy endings. After that long embrace, some catching up, and expressions of heartfelt generosity, the brothers part, saying “See you soon!”

Well, they don’t. At least, the text doesn’t record any holiday dinners or a guys’ night out. Other than getting together to bury their father, we never hear of Jacob and Esau communicating again.

Some relationships aren’t the way we wish they would be. And hanging on to the dreams or beliefs of what we think they should be, obscures the blessing of what is. A relationship doesn’t have to spark joy all the time, or even often, to be worth holding on to. It doesn’t have to spark joy for it to matter.

There will always be distance between these twins. But it will no longer be fraught. It will be free. That space allows a flow of love and connection.

An efficient way to clean out messy drawers may be to hold each object and ask, “Does this spark joy?” But when it comes to the stuff of life, a more incisive question for us to ask is, “Does this smell like heaven?” meaning, “Does this have some kind of sacred purpose?”

Will holding on make a difference to me? To those I love? To those in my future?

Will letting go help me live with my pain, rather than cause pain?

Will holding on energize me forward or pull me back?

Will letting go give me greater strength and buoyancy to swing on that high bar hyphen that is my life?

Simone is a once in a generation, perhaps a once in all time, talent. The rest of us are sometimes Jacob – carrying the shame of having wounded those we love, and sometimes Esau – carrying hurt heavily inside us.

As we draw to an end of our time together on this Kol Nidre, let’s take just a moment to prepare for tomorrow’s task of beginning to hold and let go. If you’re comfortable, close your eyes.

First, I invite you to reflect on something that takes effort, but brings you a sense of purpose –

a relationship, an activity, a mission – something that you want to hold onto with greater intention. Now, take a few breaths, and, concentrating on your inhales, deeply breathe that in.

Now reflect on something that you are tired of carrying – a calcified anger, a shame, a self-doubt – something you are ready to put down and leave behind. Take a few breaths, and this time, concentrating on your exhales, sigh that out.

Perhaps after services, we will write these down. Or maybe tuck them away in neatly organized drawers of memory. Either way, we will pull them back out tomorrow and get to our sacred work.

Look! The gates of the new year are swinging open, inviting us into possibility!

We can learn.

And when we do, we can practice.

And when we do, we can change.

1 https://www.thecut.com/2016/08/simone-biles-snapchat-what-shed-save-during-a-fire.html

3 Yehuda Amichai, “Late Wedding,” The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai

4 https://www.today.com/news/simone-biles-competing-tokyo-olympics-be-voice-abuse-survivors-t214955

5 “Hovering Above the Pit,” Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust, ed. Yaffa Eliach

6 Genesis 27:40

7 Yoma 80a

8 “Striving With God,” Gospel Medicine