Anti-Semitism In Our Time

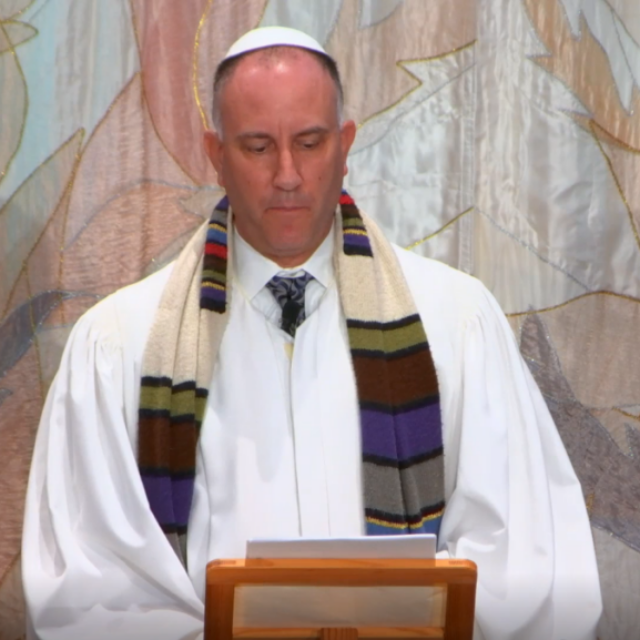

Sermon by Rabbi Joel M. Mosbacher on Yom Kippur, 5782

September 16, 2021

Sermon Text:

Some of you might have heard me share this story earlier this summer.

As many of you know, I grew up in the Chicagoland area. We lived in the southern suburbs, and would often visit my dad’s parents in Skokie, north of the city.

I was 8 years old when a group of Neo Nazis threatened to march in Skokie. When I heard about the planned march, I remember being scared for my grandparents. I grew up in a Reform synagogue that had lots of members who were holocaust survivors. Several of my Hebrew school teachers had numbers tattooed on their arms.

I wonder now, looking back, what my Omi and Opi, who were 13 or so when the Nazis came to power in Germany, what they thought about the planned march in Skokie, their very Jewish adopted American home town.

I actually don’t know what came to their mind; I never asked them.

I wonder, though—did they think, “here we go again?”

For me, at the time, perhaps because I never remember personally experiencing it, I do remember thinking, “I thought anti-Semitism ended after the Holocaust.”

Boy, was I naive.

In our time, the incidents of anti-Semitism are almost too numerous to count, and far too many to ignore.

The Tree of Life synagogue shooting, the Poway synagogue shooting, the neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville.

A 29-year-old man punched, kicked and pepper-sprayed in Times Square a few months back.

In Los Angeles, five Jews attacked by people waving Palestinian flags.

Jewish institutions vandalized.

Synagogues receiving threatening phone calls.

Jews harassed on social media.

Anti-Semitism might be called the oldest hatred, but, to my deep sadness and dismay, it is also a current event.

According to a study done by the Anti-Defamation League,1 there has been a 63% increase in these attacks in the last few years, among the highest count since the ADL began keeping statistics in the 1970’s.

There is a part of me that is surprised; a part of me that asks incredulously, “Even here in America?”, and then a part of me that responds wearily, “Yes, here in America.”

American democracy and religious freedom have been a gift to the Jewish people, to my family, and, I’m sure, to many of your families, allowing us to thrive here as we have nowhere else in the history of our Diaspora.

And yet, we know a more troubling legacy.

Here in America: where Father Charles Coughlin spewed Jew hatred on his 1930’s radio show to thirty million weekly listeners.

Here in America, where aviation hero Charles Lindbergh spoke at a rally of the isolationist “America First Committee” in 1941.

And recall Henry Ford, who received the highest honors from Adolf Hitler for his promulgation of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

“But wait,” the first part of me says, “just because there is Jew-hatred in our past doesn’t mean it’s in our societal DNA. That was then; this is now.”

And then that other part of me, wearier still, says one word, “Charlottesville;” white supremacists, the Klan in khakis, chants of “Jews will not replace us,” armed extremists gathered outside the Reform synagogue in Charlottesville while the Jews prayed inside.

In the twenty-first century, here in America.

Racism and anti-Semitism marched in lock step in Charlottesville, and reminded us of the truth we learn and forget, and now in 2021 learn again: anti-Semitism flourishes in any hothouse of intolerance, and grows robustly alongside other hatreds, whether those hatreds seem directed towards us as Jews or not.

Racism, nativism, homophobia, Islamophobia – all should ring a shofar blast of alarm not only for the decency of American society, but for the safety and wellbeing of the Jewish community.

These past few years have taught us yet again: it is both morally repugnant and practically misguided to hunker down while others are targeted, let alone to support those who do the targeting.

But what exactly is this phenomenon we call anti-Semitism?

The term itself was popularized by a Jew-hater named Wilhelm Marr in 19th century Germany who sought to racialize the hatred of Jews beyond its religious roots.

Sociologist Helen Fein defined it as a “persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collectivity.”2

We use the word to refer to Jew-hatred in all its forms – from a swastika defacing my niece’s school in Georgia just last week to internet screeds about Jews controlling the global economy; from the religiously motivated anti-Judaism of the ancient and medieval church, which saw Jews as the source of ultimate evil for their rejection of Christianity; to the 19th century racial theories which saw Jews as corrupting the purity of the white race and eventually gave rise to Nazism; to the political uses of anti-Semitism today by left and right alike.

In important and recent books, Professor Deborah Lipstadt of Emory University and New York Times columnist Bari Weiss each emphasize that anti-Semitism, for all its diverse expressions, always asserts a core conviction of conspiracy: of Jews as a maliciously intelligent force, small in number, cosmopolitan in alliance, with the ability to compel the will of the powerful and wreak havoc around the world.3

Anti-Semitism is deviously flexible in its form.

Weiss calls it, “an ever-morphing conspiracy theory in which Jews play the starring role in spreading evil in the world.”

“In the eyes of the anti-Semite,” she writes, “the Jew is…whatever the anti-Semite needs him to be…the symbol of whatever a given civilization defines as its most sinister and threatening qualities.”4

Think about it – to the anti-Semitic country club capitalist, Jews are a bunch of Commies inciting the rabble; but to the anti-Semitic leftist, Jews oppress the common man by controlling all the capital.

Eric Ward, an African American community organizer and activist, argues that, to white supremacists, Jews are considered traitors to the white race, and that our international scheming and perverse sympathies are the only explanation for the ascent of all those innately inferior people of color in America.5

It is out of all of these pernicious dynamics, out of the latest conspiracy theories about Jews, that my grandparents, and millions of other Jews with a 1000 year history in places like Germany, were oppressed, expelled, or murdered during World War II.

And in many ways, it is this dynamic and these conspiracies that continue to threaten us today.

Ward, the Black organizer and activist, tells the story of visiting what is called a “Preparedness Expo” at a convention center in Seattle in 1995.6

Ward attended as a field organizer for the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment, a six-state coalition working to reduce hate crimes and violence in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain States region.

The coalition does a lot of primary research, often undercover.

A cardinal rule of organizing is that you can’t ask people to do anything you haven’t done yourself; so Ward spent that weekend as he spent many—among people plotting to remove people like him from their ethnostate.

It helped that, despite its blood-curdling anti-Black racism, at least some factions of the White nationalist movement saw Ward as a potential ally against their true archenemy.

At the expo that year, a guy warily asked Ward why he was there.

Ward told him that he had come on behalf of a few brothers in the city who wanted to resist the federal government, and were there to get educated.

Ward said he hoped the guy wouldn’t take it personally, but that he didn’t shake hands with White people. The guy smiled; he totally understood.

“Brother McLamb,” the guy said, “says we have to start building broad coalitions.”

Together they went to hear Jack McLamb, a retired Phoenix cop, who ran an organization called Police Against the New World Order, make a case for temporary alliances with “the Blacks, the Mexicans, and the Orientals” against the real enemy, the federal government controlled by an international conspiracy.

McLamb didn’t have to say who ran this conspiracy, because it was obvious to all in attendance.

Contemporary anti-Semitism, according to Ward, does not just enable racism, it also is racism, for in the White nationalist imagination, Jews are a race—the race—that presents an existential threat to Whiteness.

The bottom line: White supremacists, who, amongst themselves have plenty of disagreements, agree on one thing: Jews are not White. And, Ward says, we ignore that at our own peril.

I’m honored that Eric Ward will be speaking later today at 3:30pm to explain the importance of understanding that anti-Semitism is not a sideshow to racism, as much as it is the fuel that White nationalism uses to power its anti-Black racism, its contempt for other people of color, its xenophobia, its misogyny, and the other forms of hatred it holds dear.

As author Jo Glanville writes,7 “Anti-Semitism never goes out of fashion. It adapts endlessly to the anxieties of the age. Pandemic? Jews are behind it. Immigration? Jews are orchestrating it. Terrorist atrocity? A Zionist plot.”

We perhaps know it best in its right-wing extremist forms: Charlottesville and its tiki torches, internet harassment and death threats to Jewish journalists, the domestic terrorism of neo-Nazis and the white supremacist movement.

Political leaders like our former President, and like Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Bobert in recent months, have all perpetrated the age-old kinds of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that only serve to give cover to, and inflame those who would lash out at Jews and blame us for the problems of society.

But anti-Semitism has found a home on the left as well.

We see much of its current manifestations on college campuses, where Jewish students and professors who express support for Israel can encounter harassment or exclusion from progressive spaces and movements.

As you have heard me say before, and as I deeply believe, Israel, like every other sovereign state, can and should be criticized when it doesn’t live up to its human rights obligations, to the aspirations laid out in its own declaration of independence including toward its own Jewish and Palestinian citizens and residents — as well as toward those living under its occupation.

Criticism of Israel as a country, bound by the same international law as other countries, is not inherently anti-Semitic.

But it is anti-Semitic, and beyond the pale, as Rabbi Jill Jacobs teaches, to equate Jews or Jewish institutions with the State of Israel, or to take out anger about Israel’s actions against Jews or Jewish institutions, or to apply to Israel the classic anti-Semitic tropes such as the visual of the octopus controlling the world with its tentacles, or to deny Jewish history in Israel, or to call for the expulsion of all Jews from Israel, or to demand that Jewish students on campus disavow any connection to Israel before joining progressive coalitions or taking any part in student government.8

My friends, as New York Times reporter Emma Goldberg has written, we Jews have lived a “dual history of trauma and privilege.”9

Yes, we have achieved and experienced a notable measure of success and status in American society – but we know too well that such success is no guarantee of protection against (and sometimes invites) forces of scapegoating and hatred.

So how shall we combat anti-Semitism in the year 5782, now 10 days old?

First, of course, we expand our physical security.

We, like thousands of Jewish organizations across the country, have enhanced our security measures significantly here at the synagogue over the years.

I wish that we didn’t live in a world where a synagogue would need armed security guards, but we do.

At the same time, we recognize that a synagogue that becomes a fortress is no longer a synagogue.

I am grateful every day, and I hope you are, too, for the outstanding security professionals who protect us, and for the excellent team of lay people and synagogue staff who help us strike the best possible balance between keeping people safe, and helping people feel welcomed by this community of meaning, connection, and purpose.

Second, we must continue to call out anti-Semitism from wherever it comes.

If you find yourself rationalizing or minimizing the anti-Semitism of someone from your political party, while railing against the anti-Semitism of a different political party, then you are reducing anti-Semitism to a partisan political cudgel, and cannot claim to be taking it seriously.

One of the first places we can call out anti-Semitism, whether tweeted from the halls of Congress or dog-whistled from the White House, is among our own political allies.

Third, I’d actually submit for your consideration, ironically, that we take up the recommendation of the white supremacist Brother McLamb that Eric Ward met at the Preparedness Expo.

We have to start building broad coalitions.

Jews cannot stand alone in the fight against anti-Semitism.

We need to see our fate as Jews as inextricably linked with the fate of others, and help them see that ours is linked with theirs.

We must show, not just tell our neighbors and non-Jewish friends, about the beauty of our traditions.

We must share our sacred stories with them, and then listen, with strong backs and open hearts, as they share their sacred stories.

As individuals, we should invite them to Seders and to services and to our Shabbat dinners, and we should accept their invites to Church celebrations and Iftar dinners.

As a congregation, we can deepen our interfaith organizing efforts in Manhattan Together, that bring us into real deep relationship and sacred action with peoples of many different faiths and backgrounds.

When we see other people as human beings and they see us, it is much harder for us to demonize one another.

Fourth, let us lean into the beauty of Judaism itself.

Deborah Lipstadt, someone who has been, as she calls it, “swimming in the sewers of Jew-hatred and holocaust denial” for 40 years, said at our most recent Reform Movement Biennial convention that, while she is of course deeply concerned about the trend towards increased anti-Semitism, she is equally worried about what we Jews might do to ourselves because of anti-Semitism.

“Concern about anti-Semitism cannot become the leitmotif, the cornerstone of our Judaism,” Dr. Lipstadt said.

She shared the story of one of her students, a senior at Emory who Dr. Lipstadt had known for 4 years, who suddenly decided to begin wearing a kippah.

When the professor asked him why, he replied, “There have been so many attacks on Jews recently. I’ve decided that every time there is an anti-Semitic attack, I am going to wear my kippah so that I can show the anti-Semites they can’t frighten me.”

When she told this story, the 5000 Reform Jews at the Biennial plenary applauded.

Dr. Lipstadt smiled a wry smile and said, “I had a slightly different reaction.”

She went on to say that, while she admired her student’s chutzpah, his desire to show his identity and not cower in fear, she said that her heart broke a little inside, because he had allowed anti-Semites to determine when he felt Jewish.

“They were controlling his Jewish identity… he was motivated by the ‘Oy’ of being Jewish, not by the joy of Jewish life. That’s not my Judaism,” Dr. Lipstadt said, “and I don’t want it to be his.”

Lipstadt, a fearless warrior against anti-Semitism, called on us to live affirmatively joyous Jewish lives, to celebrate Shabbat, to honor our parents, to shoo away the mother bird from the nest before taking the eggs, to be concerned about the most vulnerable amongst us, to let our land lie fallow every seven years, to pursue justice with just means, and to maintain an indelible connection to the State of Israel, even when we disagree with its policies.

In short, she called upon us to build a Jewish identity based on “what Jews do, and not on what is done to Jews.”10

Lastly, as real and stubborn as the existence of anti-Semitism is, we need to keep it in perspective.

Dr. Lipstadt reminds us that even the alarming upsurge of anti-Semitism in Europe today does not come close to the anti-Semitism of pre-Holocaust Europe with its state-sponsored persecution, and is actually accompanied by encouraging signs of Jewish rebirth.11

After the shooting at Tree of Life, and after Poway, and after Charlottesville, and after attacks in Los Angeles, and here in New York, the outpouring of love and sympathy and solidarity for the Jewish community was profound, with very public support coming from the general population, from politicians of all political persuasions, from religious leaders of every faith tradition, and from cultural figures of all kinds.

My friends, the presence of anti-Semitism is painful and enduring. The challenge before us is to be vigilant, but not fearful, because fear will distort who we are.

We can’t let anti-Semitism drive us into tribal isolation, drawing the wagons into a circle, hopelessly distrustful of the world around us.

As Rabbi David Stern has taught,12 if the targeting we experience as a minority leads us to fear and target other minorities, the anti-Semites have won.

If the only message we give to our children is, “Be Jewish, because your ancestors suffered and died for the privilege,” the anti-Semites have won.

If the only Jewish cause that excites us is fighting against our persecutors rather than fighting for our values, then the anti-Semites have won.

If anti-Semitism breaks our hearts, but does not break them open to the suffering of others, then the anti-Semites have won.

Because in the end, the destiny of the Jewish people does not reside in some neo-Nazi meeting, or a hateful pamphlet, or a demagogic politician, or even in an act of terror.

It resides right here, in this ark, in this sacred community, in our hearts, and in our hands.

In the face of the oldest and most adaptive hatred, the best and most triumphant answer we have to anti-Semitism is a proud and vibrant Jewish life.

Like the lives my Omi and Opi led.

They could have been bitter and angry- they had every right to be.

They could have taught their children and grandchildren and great grandchildren to hide their Judaism, or taught us to be Jewish so as “not to give Hitler his final victory.”

But instead, they shared their difficult stories of suffering and survival and they lived full and rich and joyous Jewish lives supported Jewish causes and taught their progeny to live in the world and fight for the rights of all people.

Yes, sometimes the answer to anti-Semitism needs to come in the form of added security and greater vigilance at the door.

But if you consider that the goal of the anti-Semites might be not an explosion, but simply the erosion of Jewish self-confidence. If you remember that if this world of ours is a university, Judaism is now more than ever an elective, and each person opts in or out at will; then our shared responsibility to bring Jews of every age into a sense of Jewish meaning, connection, and purpose might well go farther than a thousand guard houses in securing the Jewish future.

I offer this sermon because I think anti-Semitism is serious.

And, I offer this sermon to bring you my favorite quotation from the late Rabbi Harold Schulweis who said, “The Holocaust is our tragedy; [but] it is not our rationale.”13

We are not Jews because of anti-Semitism.

We are not Jews because of Hitler, or even despite him.

We are Jews because of God, because of Torah, because of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv; because of our commitment to justice and compassion and human dignity; we are Jews because of history and song, because of tzedakah and Shabbat and Yom Kippur; and because of the kugel and the arguments that await at your Break Fast tables tonight.

As I close, here are two things I’ve been reminded of in recent months.

Number one: ant-Semitism is alive and well even in bastions of Jewish life like New York City.

We must not be blind to or naive about that. We must battle it and defeat it for our own sake, and for the sake of other vulnerable communities.

And, number two: unlike my grandparents in Germany in the lead up to the holocaust, we Jews, in our time, are not alone, unless we choose to be.

Our security team will keep us safe.

Our coalitions with others will stand with us when we need them, and we’ll stand with them when they need us.

And our embrace of Judaism will bring depth and richness and thickness to a Jewish identity that has endured and outlived and outshined every hatred.

May the Holy One of Blessing, and all of God’s people, be there for us as we are there for them now and always.

G’mar chatima tova.

1 https://www.adl.org/news/press-releases/anti-semitic-incidents-remained-at-near-historic-levels-in-2018-assaults.

2 Deborah E. Lipstadt, Antisemitism: Here and Now (New York: Schocken Books, 2019) p. 15. Italics in original.

3 Lipstadt, pp. 16-17

4 Bari Weiss, How to Fight antisemitism (New York: Crown, 2019), p. 31

5 Eric Ward, “Skin in the Game: How Antisemitism Animates White Nationalism,” Political Research Associates website, 2017.”

6 Ibid.

7 “Looking for An Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism,” p. 4.

8 “Looking for An Enemy: 8 Essays on Antisemitism,” p. 86.

9 Emma Goldberg, “White Jews have found privilege in America. Black communities haven’t” https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/after-farrakhan-mallory-confronting-america-s-black-jewish-divide1.5958910/1.5958910.

10 https://www.urjbiennial.org/livestream.

11 Lipstadt, p. 108.

12 Rabbi David Stern, Rosh Hashanah sermon 2019.

13 Rabbi Jack Stern, The Right Not to Remain Silent (New York: iUniverse, Inc., 2006), p. 155.