From the book of Ruth to Us: Post Traumatic Growth

Sermon by Rabbi Joel M. Mosbacher on 1st Day Rosh Hashanah, 5782

September 7, 2021

co-written with Rabbi Ken Chasen of Leo Baeck Temple, Los Angeles, CA

Sermon Text:

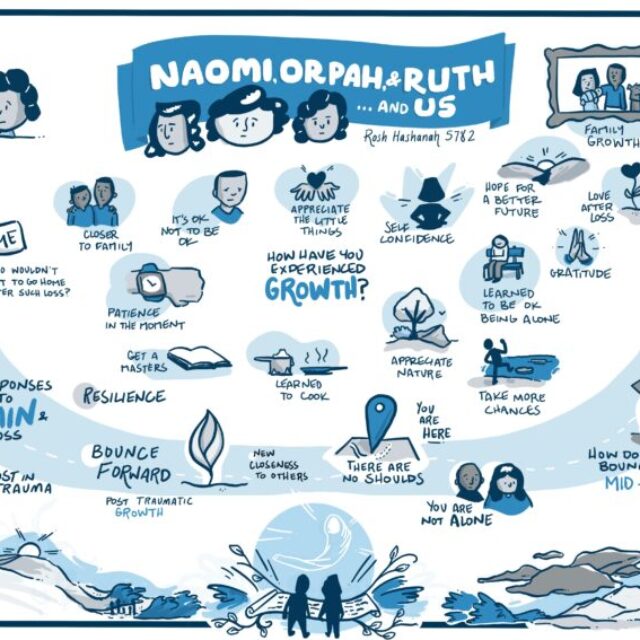

(Today we have Joe, a live artist from Dayton, Ohio with us on line. Joe will be listening throughout the next several minutes and bringing what we share to life in a visually compelling way.)

A plague strikes without warning.

Communities are broken apart as people leave their homes seeking a safer place to live. Close families are separated from one another. Whole workforces lose their jobs. Everything people thought was secure and solid was suddenly thrown into question.

And so much death. So much death.

I speak, of course, of a story that took place 3000 years ago in the biblical book of Ruth.

The book tells the story of Ruth and Orpah, two Moabite sisters who married brothers from Judea called Mahlon and Chilion.

In the story, the brothers and their parents, called Elimelech and Naomi, had left their home in Bethlehem, fleeing a terrible famine.

They moved 50 miles east to Moab, seeking greener pastures for their flocks.

Sadly, though, shortly after their arrival, having experienced the trauma of leaving behind their ancestral home and everything they knew, the patriarch of the family, Elimelech, dies suddenly.

His sons, Machlon and Chilion, eventually marry those two local women—sisters from Moab, Ruth and Orpah, but then, a few years after that, tragically, both Machlon and Chilion die as well.

Suddenly, in a patriarchal society where marriage is the only security women can rely on, Naomi, Ruth and Orpah are all left as widows.

Here in the book of Ruth, we only hear the story of this one family fleeing the famine in the land of Canaan; no doubt there were hundreds of stories, thousands even, of loss and death and pain beyond imagination.

To read the book of Ruth is to wonder:

How did they experience that upheaval, and what did society look like on the other side, after the plague had passed? What did their lives look like after all they had been through?

A plague strikes without warning.

Communities are broken apart as people leave their homes seeking a safer place to live. Close families are separated from one another. Whole workforces lose their jobs. Everything people thought was secure and solid was suddenly thrown into question.

And so much death. So much death.

I speak, of course, of the trauma that the entire human race has endured for these last 18 months—a trauma still taking new shapes and bringing new losses, as Rabbi Reines spoke of last night even as we welcome the arrival of this new year 5782.

We have been through so much in the last year and a half. And the anguish of this time won’t just disappear, even when our masks finally come off for good, even when this sanctuary is once again at full capacity filled with congregants on a Rosh Hashanah morning.

Depression, anxiety, substance abuse and suicides have all risen during this time.

Our first responders have experienced whole other layers of agony. And our essential workers, the ones who never stopped making our lives as secure and safe and as educated and well-fed as possible—they’re burnt out.

How will we respond in this time, individually and collectively? How will things look for us as we eventually emerge from this crisis? How will we approach the future?

For a moment, let’s look back 3000 years – to Naomi, Orpah and Ruth – to see how they responded to all that they had lost. From them, we might be inspired to enter 5782 with a sense of hope and possibility.

Back in Moab, three traumatized women, having endured the stresses that thousands of families were suffering at the time, each responded in different ways.

Naomi, devastated by the loss of her husband and two sons, heads back to her native home in Bethlehem, which she surely wishes she had never left. The famine had cost her everything. So it is no surprise that she chooses to spend her final years grieving at home.

And who among us wouldn’t want to just go home after such heartbreak?

After all, when my family first finally stepped onto a plane this past July, it was to visit Elyssa’s family in Los Angeles for the first time in two years. Now, even with the unprecedented hardship of the pandemic, my family hadn’t lived through even a hint of the kind of ordeal that had stricken Naomi, but still, we weren’t itching to fly for business or vacation.

But that first magnetic draw to re-enter the world for us was to go to family. We needed to feel the love of those in whose lives, our lives have been rooted from the very start.

When Naomi arrives back in Bethlehem, she asks everyone to call her Marah – bitterness – instead of Naomi, which means pleasantness. And that’s the last we know of her story.

Given the near impossibility of the task before her – to carry on somehow in the aftermath of losing her entire family – not one of us would question why she sees her very identity as bitter.

Orpah, for her part, also chooses to go home… that’s Moab for her. She seeks the comfort of the familiar, the safety of her own family and friends, the gods she had grown up with; She seeks to begin again, following the loss of her young husband. Again, it’s a choice that practically any one of us in her shoes would likely have made.

But beyond her decision to start over where she came from, we also know nothing of the unfolding story of Orpah’s life. We are left to hope that returning to her roots enabled her to regain her balance, recover from her heartbreak, and resume her life with some modicum of peace.

So that leaves Ruth – the woman for whom the book is named… one of only two books of the Hebrew Bible’s thirty-nine, in fact, that is named for a woman. What becomes of Ruth?

Well, we know that Naomi, after the death of her two sons, encourages both of their widows, sisters Orpah and Ruth, to go home to Moab, to their family. But only Orpah follows her mother-in-law’s urgings.

Ruth, on the other hand, stays with Naomi, following her back to Bethlehem.

In one of the most memorable lines in the entire Hebrew bible, Ruth says to her grief-stricken mother in law, “Do not urge me to leave you, to turn back and not follow you. For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried.1”

Seeing through the lens of the collective human pain that we’ve all been through in the last year and a half, I read Ruth’s words with new appreciation and inspiration. For in the face of unimaginable loss and uncertainty about what her future holds, Ruth dives deeper into relationship with her mother-in-law; she finds new strength through the experience of loss; she sees new possibilities in her future, and she undergoes a spiritual transformation. It is as if she gains a new appreciation of life even in the aftermath of loss and devastation – perhaps even because of it.

Frankly, I don’t know how she does it. And I wonder: could I do what Ruth did? Could we?

My friends, this a question that we’ll all have to answer in this new Jewish year, 5782.

To explore that question, I sought out the research of numerous psychologists who have studied the ongoing life stories of people who have endured all kinds of pain.

Researchers tell us that there are three basic human responses to the kind of experiences we’ve been through in the last year and a half. Some survivors of physical and emotional wounds struggle mightily and persistently: they develop what has come to be known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; they face debilitating depression and anxiety; they have difficulty functioning. They descend, through no desire or fault of their own, into bitterness brought on by their ordeal, as the biblical Naomi did following her multiple bereavements.

Others experience resilience– something I have preached about before from this pulpit. They bounce back to the way they were before the trauma. This seems to be Orpah’s hope in heading back home to Moab – to the memories of her life before she had ever gotten married or widowed.

But scientists describe a third possibility – another option besides getting lost in trauma or bouncing back from it. It seems that some people figure out how to bounce forward. Multiple studies show that more than half of people who experience a traumatic event report at least one positive change in their lives in the aftermath of what they endured, compared to less than 15 percent of those who develop PTSD.

Two scientists in particular, Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun, coined a term to describe this phenomenon I had never heard before: they call it Post Traumatic Growth.

Of course, the notion that suffering and distress can potentially yield positive change is thousands of years old. Teachings from Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and other faiths speak to the transformative potential of suffering, as do the writings of novelists, dramatists and poets.

What Tedeschi, Calhoun, and others have formally learned from their studies is that, during and after the most trying times, some of us see growth in ourselves in a whole range of areas of our lives.

Some experience a change in the priorities in their life, or an intensifying of faith, or an untapping of strength, or the development of new interests and new capacities.

Sometimes, it is upheaval that unleashes our willingness to change those things we long knew needed changing. In moments like these, some people discover a new closeness with others, a new compassion, a new readiness to accept and give help and support.2

In short, scientists are only now coming to codify what Ruth modelled for us 3000 years ago. It turns out that Ruth is the Bible’s exemplar of post-traumatic growth.

This morning, I want to ask you all some questions about if or how you feel you’ve grown during this previously unimaginable time. But before I do that, I want to be clear about two things.

First, to the extent that we’ve seen growth in ourselves in and through this time, I imagine that every single one of us would give back that growth if we could also give back the trauma we’ve been through.

And second, there are no “shoulds” about where you are at emotionally right now. We’ve all experienced this time differently; no one can or should tell how to feel.

What I do know, and what I am so happy to say is that you’re here; you’ve made it this far in the journey. And because of chosen to be a part of this community of meaning, connection, and purpose, you are not alone.

You’re propelling yourself into this new year, with your spiritual community, bravely asking the questions that this season of the Jewish year places before you, after a year and a half like nothing you could ever have imagined.

And you do not need to compare yourself to Ruth, or to anyone. Yes, Ruth provides some blessed inspiration on a day we count upon to inspire us – but the only standard by which our tradition calls us to be judged is ourselves.

So wherever and however you find yourself this morning along the spectrum of suffering, resilience and growth – from Naomi to Orpah to Ruth… to you – I see you.

And maybe, just maybe, your commitment to this holiday season – this enterprise of staring at our souls and telling the truth about what we see – might surprise you by catalyzing real growth.

What is for sure is that it will not be easy. After all, how does a person seek post-traumatic growth when the trauma is still going on?

As Rabbi Reines reminded us last night, we know we are never fully and completely “post-trauma” in our lives. When Ruth makes her choice to stay with Naomi in the land of Judah instead of returning home to Moab, she surely hopes that her days of suffering have ended with the death of her husband.

But she is heading to a foreign land, with a language and religion and culture she doesn’t know – and she and Naomi arrive in dire poverty, exacerbating the powerlessnessand disadvantage that came simply with being a woman in the Ancient Near East.

In short, Ruth was both post-trauma and mid-trauma… just as we are in this pandemic.

In one strange way, our predicament a year ago was simpler in a certain way than our current one. That is to say, there was absolute clarity a year ago, about for example, where you all sadly needed to be on the high holidays. The most difficult decisions were made for us by our places of work and public gathering.

Now, the choices about what to do or not do are largely up to us, and they’re extremely hard choices to make. And nobody knows what comes next. All the uncertainty might leave us paralyzed, afraid to risk, afraid to grow.

Ruth faced incalculable risks by accompanying Naomi to Bethlehem instead of heading home to Moab. And yet she took that leap of faith.

And, we are taught, she found love again. She rose to prosperity again, from the depths of destitution. And she became a mother – then a grandmother, and then the great-grandmother of King David, from whose line we are taught the Messiah will one day come.

There is inestimable power in the determination to grow when we are at once post-trauma and mid-trauma, just as Ruth was; just as we are right now. And part of that power comes from being able to tell our stories.

Many of you have already shared your sacred stories of this time with me, and we will hear more from some of our fellow congregants during this holiday season.

This coming Friday night, I hope you’ll join us online or in person for services at 6:15 as we are joined by Dr. Betsy Stone, who has been a profound teacher to me and so many others on the subject of post traumatic growth.

And today, for a few minutes, I’d like to invite you to share your story with your fellow congregants as we begin to tell our collective story. I’d like to invite you to think for a moment about the ways in which you might have experienced growth in your life since March 13 of 2020, despite the challenges of the last many months.

In these months,:

- What personal strengths have you discovered?

- Have you discovered a new appreciation of life?

- Which relationships do you most rely upon?

- To what new possibilities in your life were you awakened?

- How has your spiritual life grown during this time?

Think for a moment on these questions.

This morning. I’d like to begin the process of collectively sharing these stories.

If you’re watching online, I’d invite you to share, if you’re willing, by following the instructions on your screen. And if you’re here in the sanctuary, I will invite you to share by telling my colleagues who will fan out throughout the congregation.

And Joe will help capture what we share.

Have you experienced growth in this time? If so, how?

My friends, in our machzor, there is a prayer that could have been written for just this moment. It says, “Our God and God of our ancestors, sound a great shofar for our liberty and raise a banner to gather our exiles. And bring near our scattered people from among the nations, and gather our dispersed from the ends of [the] earth.

Here [through this art], we have the first banner of our ingathering.

Even as we tell the story of this challenging time, even as we long to emerge fully, from our isolation from one another, may 5782 be a new year of health, safety, and ingathering.

And now, we hear the sound of the shofar, symbolizing our slow, gradual emergence, and yes, perhaps, even growth, as we hope in this new year to find ourselves liberated from this time of challenge.

1 Ruth 1:16

2 “The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma.” Tedeschi and Calhoun, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 1996.