Make meaning,

pursue purpose,

spark connection.

Temple Shaaray Tefila is a dynamic, welcoming Jewish community on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Whether you are seeking connection, community, purpose, learning, or a place to call home, you will find it here. Grounded in Reform Jewish values, we show up for each other and for the world.

Celebrate Shabbat with Shaaray Tefila!

Join us in person or via livestream for a Shabbat experience filled with meaning, connection, and purpose. Click the button below for our most up-to-date listing of upcoming services.Erev Shabbat Services

Fridays @ 6:15 pmSaturday Morning Minyan

Saturdays @ 10:15 amShabbat Torah Study

Saturdays @ 12:00 pm

Spotlight

Keep your eyes here for the most important happenings at Shaaray Tefila right now.Upcoming Events

Meaningful experiences to connect with Jewish community, ritual, history, and heritage.

Mon

26

Jan 2026

Torah & Animation with Hanan Harchol

@ 7:00 pm

Wed

28

Jan 2026

Torah Talk

@ 12:30 pm

Wed

28

Jan 2026

Resin Tray Workshop with Gold Geodes

@ 6:00 pm

Thu

29

Jan 2026

Mah Jongg & Canasta Game Night

@ 6:00 pmInspiring kids and families to love Jewish life, learning, and community.

Birth-18 mos

Parenting Program

Classes for families and their children from birth to 18 months structured to highlight child development, explore the joys and challenges of parenting, and foster a sense of community.

Learn more

Ages 2-5

Nursery School

A nurturing environment that allows children ages 2-5 to build friendships with their peers, experience Jewish rituals, traditions, and values, and become curious and enthusiastic learners.

Learn more

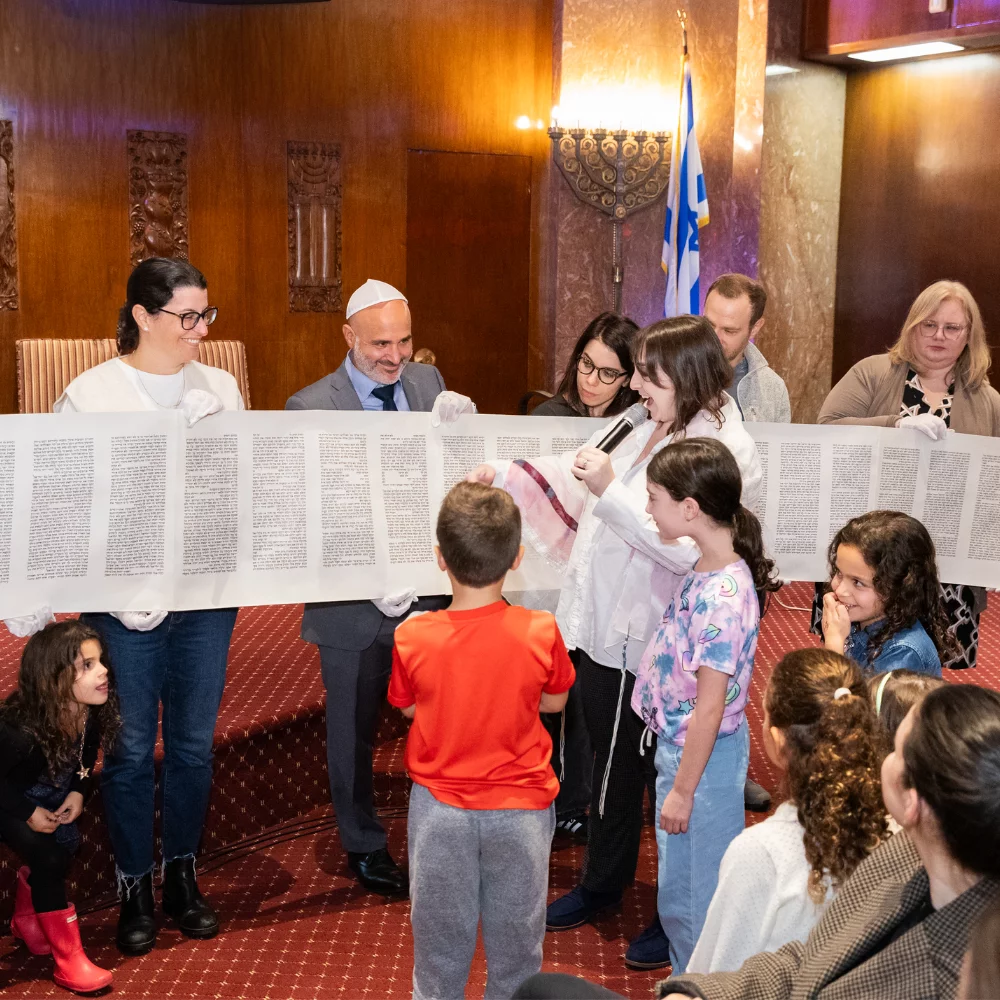

PreK-Grade 12

Religious School

We strive to help students love being Jewish. We believe that children who feel loved at synagogue will grow up to be adults who are drawn to places where Jewish learning and living happen.

Learn more

Get involved.

Make a positive impact and connect with fellow congregants in the way that feels right for you.

Volunteer

Help bring compassionate outreach to our members in times of need as well as moments of joy, offering comfort and connection through acts of loving kindness.Caring Committee

Learn more

Connect

Learn, deepen relationships, and grow through thoughtful and tasty food-related experiences and programming.Manna

Learn more

Volunteer

There are adults and children in our neighborhood that are hungry - we can help! Come pack and provide nutritious meals and healthy snacks for our neighbors in need.Backpack Buddies & Soup Kitchen

Learn more

Worship

Add your voice to Shaaray Tefila! Join our volunteer congregational adult choir to connect with other music lovers, experience Jewish music, and perform at services.Kol Rinnah Choir

Learn more

Connect

Join a small group - or start your own - around an area of interest and deepen your relationships across the congregation.Shaaray Circles

Learn more

Latest Posts

Stay informed with messages, stories, and wisdom from Shaaray Tefila.

Our dedicated clergy and caring community are here for you.

At Temple Shaaray Tefila, we understand the importance of belonging. Our clergy team and community are here to provide you with the care and support you need, whether you're facing a personal challenge, marking a moment of joy, or looking for partners in Jewish ritual and practice.

Become a member

Temple Shaaray Tefila

A Jewish home for all who seek meaning, connection, and purpose.

© All rights reserved.

-cx9fdsktr7.webp)