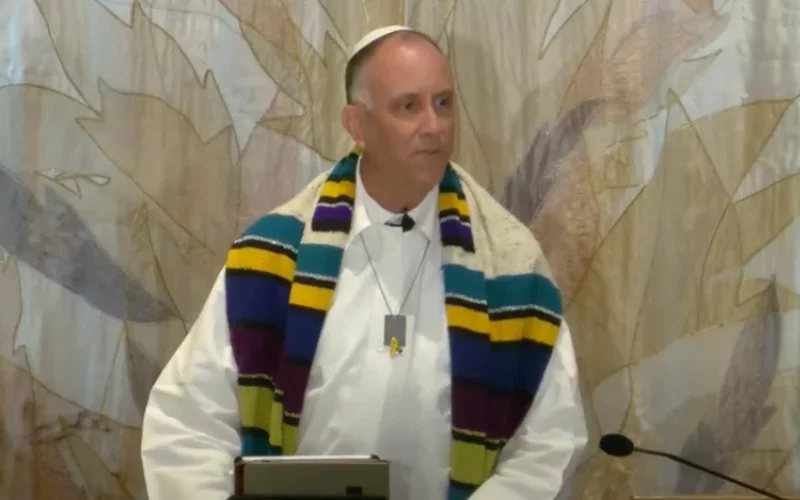

WATCH: Rabbi Mosbacher's Sermon on Yom Kippur Morning 5786

An Uncivil War

Sermon by Rabbi Joel Mosbacher on Yom Kippur

October 2, 2025 / 10 Tishrei 5786

To view the entire morning service, click HERE.

To view the guest speaker/afternoon service/Neilah services, click HERE.

Sermon Text:

Over the summer, I asked some wise souls in this sanctuary what they needed to hear about on these holidays- what sacred story they thought I should tell today. Needless to say, if I asked 10 Jews, they had 15 opinions.

But one thing I heard alot was: we need to hear a sermon about something we can all agree on.

Each time I received that advice in recent weeks, I asked the person who made the suggestion, “Any advice about what you think that is that we can all agree on?” And a number of those people said, “antisemitism.”

And each time someone suggested that as a unifying topic for this morning’s proceedings, I wondered: are we unified about anti-semitism, its definition, its causes and its solutions? And, I’ve been wondering in these days, ought unanimity -on this or any other topic- be our highest Jewish goal?

Let’s explore these questions together this morning, and see what we can learn about what in fact unifies us as a people, what divides us, and where we go from here.

In order to do that, we need to go back– way back. We’re going to go back to a text that you think you know well, a text that brings us together each year on the evening of the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, when we gather at our Passover seders.

Every year on Passover, when the youngest child asks, “Ma nishtanah halaila hazeh?” at a deep level, what they’re really asking,“what is the story of the Jewish people?” And the beginning of the answer- the Haggadah’s answer- right after the youngest child’s shining moment – the answer that we have been giving to our children for 3000 years is:

אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי- arami oved avi- “My father was a wandering Aramean.”

Now, to my 6 year old self, who had just recited the Four Questions for the first time, this felt like kind of an anti-climatic answer. But that’s the answer that the haggadah provides.

So imagine the surprise of my 26 year old self, in rabbinical school studying the interpretations of the medieval commentator Rashi on this text. Now Rashi translates the words a little differently. He translates ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי as “An Aramean tried to kill my father.”

So which translator is right, I wondered, and which one is wrong? Is it “My father was a wandering Aramean?” or “An Aramean tried to kill my father?” And, you might be wondering right about now, why am I bothering you on Yom Kippur with a story from Passover?

Here’s why.

Because ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי is, in fact, the beginning of our sacred Jewish story. The story of our journey from slavery to exodus to Mount Sinai to the promised land is our most sacred narrative as a people. And how we understand these words, and how we handle the different ways we might interpret them, can either serve as our superpower as a people, or our kryptonite.

The familiar translation - “My father was a wandering Aramean,” teaches us that, because we have so often been wanderers, and because so often have been strangers, we must tear down the walls of injustice for all, because no one is free if we are not all free, and that it never works out better for Jews when we are alone. And our Jewish history has taught us to take this admonition very seriously.

But what if Rashi’s translation is the one we should paste into all of our haggadot? “An Aramean tried to kill my father.”

Rashi’s interpretation feels pretty faithful to our experience as Jews over thousands of years. We have been persecuted, targeted, tricked, chased out of our homes and homeland again and again and again. And because of that, we must build walls around ourselves; we must take care of ourselves to make sure that we aren’t tricked, targeted or destroyed.

Rashi’s translation says, Trust no one. Protect yourselves. And our Jewish history has taught us to take Rashi’s admonition very seriously.

So which is it? And why does it matter? It matters because my honest assessment in listening to our members during the 150 or so coffees I’ve had with you this year, is that we as a Jewish people are on the verge of tearing ourselves apart over which of these interpretations is correct.

My fear at this time in Jewish history is not only about what others might do to us. It is also about what we- as Jews- are doing to each other. Our Jewish house is splintering in ways our enemies could never accomplish alone.

What is happening inside the Jewish people seems to reflect the fractures of this country, where rhetoric radicalizes, and turns neighbor against neighbor and family members against family members. And now we, within the Jewish community, are reflecting back the same suspicion and outrage and division that threatens America itself.

So many times this year, over cappucinos and cold brews and a bourbon or three, as I’ve listened to some members speak with such derision and utter disdain for the views of other members they disagree with, I have truly felt bereft for the future of our people.

My friends, I say to you today that there is no inherent contradiction, and no inconsistency, about us protecting, valuing, cherishing and uplifting Jewish lives on the one hand, and protecting, valuing, cherishing and uplifting the lives of others as well.

Both of these translations are true– Hebraically, spiritually, experientially, and psycho-socially.

Judaism has always required both of these commitments of us as a people in moments of crisis. And to be clear, we are in a moment of crisis.

If we as a people decide that difference is intolerable, if we decide to walk away from the table, around our profound differences of opinion on Israel or antisemitism or the direction of our democracy- away from debate, away from community – we will be the generation that unwinds the covenantal bonds that have held us for thousands of years as one people with many faces.

My friends, we can disagree– disagreement is a feature of Jewish life and learning– not a bug. There are approximately 5000 arguments in the Talmud, our foundational 5th century code of Jewish law, and only something like 50 of them are actually resolved in the text.

But if I could have one wish fulfilled on this day, it would be for us to each vow not to take one more step into what already is beginning to feel like a Jewish civil war over what our “real” sacred story is, as if our story were a binary of computer code, with only ones and zeros.

My friends, I ask you on this holiest day with two different versions of our sacred story as a people, are we, can we be, unified?

This is upon us to navigate, to grapple with, and I think it behooves us to know that there are people in our synagogue– people among all Jewish communities here, in Israel, and wherever Jews dwell– who see themselves in each of these sacred stories.

We as a people have begun to settle into the kind of ‘compulsive knowingness’ that Rabbi Rubin spoke of so powerfully last night. But the argument that somehow ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי can mean only one thing or the other– we are either for making the world a safer place for all, or we are for making the world safer for Jews– is neither faithful to Judaism nor effective in combating the challenges we face as a people.

We need to take both of these interpretations literally and seriously. Because the alternative is an uncivil war that I fear is already beginning amongst the Jewish people. So let’s take them seriously– one at a time.

אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי. An Aramean tried to kill my father.

Sometimes we use this as a joke for Jewish holidays like Purim. Here’s the joke: “What’s the big message of Purim? They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat!”

Except that that joke doesn’t feel so funny anymore.

You have shared with me your fears of antisemitism that feel scarily similar to the fears we have felt as a people for nearly all of our history – ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי.

In much of our lived experience over thousands of years, we have been pursued, blamed, scapegoated, forcibly converted, expelled, and killed for being Jewish.

Many of you have shared, and I have resonated with, a fear of antisemitism rising in our city and in our country, a sense that the Jewish people are alone and isolated, and a sense of hopelessness that we can turn back the rise of antisemitism. Jews under threat for wearing a kippah, for wearing a Star of David or a hostage tag; Jews killed while worshipping at a synagogue in Manchester, England as they were this morning, on Yom Kippur.

Our hearts are broken as that news unfolds.

We see the ancient echoes– from the political left, antisemitism being used right now to exclude or physically or verbally attack Jews in academic and professional spaces, and to harass them on campus. Jews who support the existence of a Jewish and democratic state of Israel are being kicked out of progressive spaces– on causes we’ve been passionate activists on for decades. And Jews are being blamed for decisions made by the Israeli government 6000 miles away.

And from the political right– antisemitism being used as a smokescreen by those who target people of color and trans people and women and immigrants used by those who simultaneously blame Jews as the orchestrators of these so-called problems. Antisemitism is being used

right now by those seeking authoritarian power to increase racialized fear and division, deflecting blame for the failures or unpopularity of policies by offering Jews as the scapegoat.

Antisemitism is being used right now as a camouflage to damage fundamental freedoms– as a sledgehammer against free speech in the name of fighting antisemitism.

Time and again, from the right and the left we Jews have been threatened, subjugated and worse for who we are. As the grandson of holocaust refugees, I know in my bones that we need to look out for our own. We cannot take Jewish safety for granted– not in our city, and not in our country.

And then there’s the other interpretation of ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי that we must come back to. My father was a wandering Aramean.

Our ancestors were strangers, and so to make the world more whole for all of God’s creatures, 36 times in the Torah, far more than any other mitzvah, we are commanded to take care of the “other” in society.

I think of the motto of the amazing Jewish organization HIAS, what our forebearers knew as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. HIAS’s motto today is “we used to help refugees because they were Jewish. Now we help them because we are Jewish.”

I’ve heard from some members who’ve asked me why we are so engaged as a congregation in social justice work. “Is that a Reform Movement thing?” they ask, implying that, if so, maybe they don’t belong as members at a Reform synagogue.

My response is: “no, justice work is not a Reform Jewish thing– it’s a Jewish thing.”

.ֲאַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי

Because we know what it’s like to suffer, to be oppressed, to be the minority, Jewish tradition implores us to take care of those who suffer, who are oppressed, who are the minority. It is because of the struggles of our ancestors that we are obligated to help others who are struggling.

The bottom line is: both translations of ִ֔אַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי placed before us– both are true historically, legalistically and linguistically.

My friends, if we are to dismantle antisemitism, and if we are to write the next great chapter of the Jewish people, we will never do it by tearing each other down, cutting each other off, retreating to ideological bubbles or ideologically homogeneous Jewish communities. If we are to show the world how we want to be treated, let us vow on this day of vows to stay in relationship with each other when the conversations are hard– especially when they are.

This is what Jews have always done.

Our most sacred texts on the one hand teach us to love our neighbors as ourselves, and on the other hand remind us that kol Yisrael arevim zeh la-zeh- all Jews are responsible for one another. The great first century Rabbi Hillel taught one of the most quoted of Jewish maxims: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, what am I?”

And we’re about to hear the haftarah for Yom Kippur we hear every year, in which God asks the non-rhetorical question, “is this the fast I desire?... Lying in sackcloth and ashes?” No, Isaiah says: “this is the fast I desire: to unlock the fetters of wickedness and untie the cords of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free… when you see the naked, to clothe them, and not to ignore your own kin.”

We see from our own synagogue’s history that this tension– a tension that I’d argue is healthy, has been a part of this community since its inception.

In 1863, when Rabbi Samuel Myer Isaacs was the senior rabbi of a then 18 year old synagogue called Shaaray Tefila on the Lower East Side, there were heated debates within the synagogue about two things that year, according to my research recently at the New York Jewish Historical Society.

One debate was: how much Hebrew should there be in shabbat services? This was a fiery argument, if you can believe it, between two entrenched camps- one made up of Jews from the old country, and one made up of Jews who had been born in America. I can’t imagine how close those worship committee meetings must have come to fisticuffs!

And the other debate was about the Yom Kippur sermon Rabbi Isaacs gave where he made the case that freed black men, former slaves who were now serving in the Union Army, should be paid the same wages as white soldiers. This, too,was an intensely debated subject in our congregation; we were not unified.

I can’t imagine the coffees Rabbi Isaacs had with members of the synagogue at the best coffee shops on Wooster Street where Shaaray Tefila was located at the time.

But the synagogue thrived through those debates about what the right balance was– between the particular and the universal– between internal synagogue issues and the issues of the day.

They didn’t choose one side or the other– do we advocate only for ourselves, or only for others? Do we only discuss ritual matters from the bimaand in the bulletin? Or do we also engage in the political hot topics of our time?

Their answer was: we have to embrace both the particular and the universal, because both elements are essential for Jewish survival and both are essential for Jews to fulfill our mission in the world.

What should the ratio be between the two? How much should we focus on one interpretation of ִ֔ביאָ ֹאֵ֣בד ֙ימֲּאַרִ or the other? That discussion has waxed and waned, I’m sure, throughout the 180 year history of Shaaray Tefila; it’s certainly waxed and waned in the 3000 year history of the Jewish people.

And that is great news. It means that we can be responsive to the needs of the moment.

I’m guessing that those ratios looked different for Shaaray Tefila in 1939 than they did in 1863; I imagine they looked different in 1963 than they did in 1939; they look different on October 2, 2025 than they did on October 2, 2023, and they should.

We already see this balance of the particular and the universal playing out on a regular basis at Shaaray Tefila.

In 2025, at the same time as we study Torah every Wednesday at 12:30, at that very same hour we are feeding our hungry neighbors on the Upper East Side, right here at your synagogue.

At the same time as the incredible Shaaray Justice Team was beginning planning for Climate Justice Shabbat in October, they created and ran an incredible program on antisemitism with 300 people in attendance here at the synagogue two weeks ago, sponsored by many Jewish organizations in the city.

And, as we have been and remain focused on creating the most meaningful and moving high holiday services, and adult education classes, and nursery school and religious school, and teen programming, and social events, our community organizing team is focused on a forum with the mayoral candidates to be held in Queens on October 19- a forum at which we’ll be publicly asking the candidates critical questions about Jewish safety in the city.

The ratio of how much we focus on ourselves versus how much we focus on the larger world is not set unilaterally by me or by our President Michele Silverstein or any one person in the synagogue. And that’s good news, too.

That means that, if you personally are driven most of all by the more particularistic fate of the Jewish people, and you think the synagogue is not focused enough on that, you can bring your ideas and your ten friends who want to work on that with you, and we will help you bring your ideas into fruition.

And, if you are driven most of all by a more universal concern in the larger world, and you think the synagogue is not focused enough on that, you can bring your ideas and your ten friends who want to work on that, and we will help you bring your ideas into fruition.

And here’s what I would guess would happen if you brought your passion and your friends to the table. If you show up for the concerns of other members, even if their concerns aren’t your top priority, I bet those members will show up for your concerns, even if your concerns are not their top priority.

Because I have both a hope and a hunch that we care about each other at least as much as we care about our own totally valid self-interests.

I told you at the beginning of this sermon about the wise and politically diverse people I spoke to, many of whom advised me to find a sermon topic for today that we can all agree on.

At some point along the way, I decided not to do that.

At first, I thought I was making that decision because I thought that perhaps it might be a fool's errand– that it might just be impossible to do so in such a beautiful community consisting of people with lots of sacred stories and a huge diversity of perspectives.

I’d like to think for example, that we’d all agree that we want Jewish people to be safe, whether they are here, in Israel, or anywhere in the world, but the fact is that we do not agree on the question of at what cost that Jewish safety should come.

In the end, I decided not to try to seek unanimity of opinion, because what I’ve come to realize– and maybe this, ironically, is something we can all agree on! – is that unanimity is not and should not be our primary goal. We have not endured as a people for thousands of years because we always agreed.

We have endured because we refused to let go of one another, even when we drive each other batty sometimes.

As my friend Rabbi Asher Knight has said, we Jews are going to need one another, not only to endure the end of the war in Israel and Gaza, which, please God, will come soon, but also in the reckoning and the rebuilding that will follow, which may test us even more.

We will need one another to resist the poisons that already divide America and to make sure that those fractures do not hollow out our Jewish house.

Do we have to choose between looking out for ourselves or looking out for others?

Do we have to choose between remembering our history of being victims of injustice or our history of helping others who are victims of injustice?

Not only do we not have to choose, my friends, I would say that we must not choose.

Both are in the DNA of what it means to be a Jew; both are in the DNA of this 3000 year old prophetic Judaism that we are inheritors of.

.ֲאַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי

We have a history of being oppressed, and we must fight that oppression. If that’s your strongest impulse at this moment, I am so very glad that you are a member here, glad that you are joining your fellow members, your lay leaders, and your clergy and staff in fighting that fight, because it feels like the fight of our Jewish lives.

ֲאַרִמּ֙י ֹאֵ֣בד אִָ֔בי

We have a history of being the “other,” and we must fight alongside all those who are the other in society today so that we will not be alone. If that’s your strongest impulse at this moment, I am so very glad that you are a member here, glad that you are joining your fellow members, your lay leaders, and your clergy and staff in fighting that fight, because that also feels like the fight of our Jewish lives.

My friends, we are stronger as a congregation and as a people when we respect one another, talk it out, and acknowledge that our sacred story can encompass more than one thing. And when we are stronger, we can both withstand the threat of antisemitism and be a force for good in the world.

And we are weaker when we cut off one half of our sacred story. And when we are weaker, we won’t be able to make the world safer for ourselves or for others.

This, truly, is our sacred, collective story. May we cherish it, and, as importantly, may we cherish one another.

May those who come after us have the privilege of inheriting a planet for the Jewish people and for all of humanity that is safer and more righteous because we were here.

That, truly, is our task.

L’shana tova tikateivu v’ticha’teimu.

May we write and seal our sacred stories- all of them- for blessing in the book of life.